Years ago, when I began work on Peace at Last, I believed that a historical novel about Bertha von Suttner, the first female Nobel Peace Prize laureate, risked little controversy and would appeal to a broad and receptive readership. Recent developments in the United States and elsewhere, however, suggest otherwise. Today, despite the book’s explicit appeals to reason and compassion, I’m fairly certain it will be banned in certain states and foreign countries.

To explain why, let’s unpack the passive “will be banned” and identify the various actors who would call for its censorship.

For starters, there’s the American gun lobby, which has been pushing an agenda of violence, vengeance, and vigilantism under the alleged cover of “God-given” constitutional rights. A book celebrating a brave woman who demanded international disarmament and diplomacy over violence would pose a threat to the mostly-male hawks and warmongers still dominating the political discourse of the day. Numerous newspaper and magazine journalists have recently written about enraged readers who verbally harassed and physically threatened them over their views on gun rights and/or regulation. Meanwhile, the epidemic of shootings in the United States claims more and more innocent lives.

Bertha von Suttner was no stranger to knee-jerk reactionaries. “Large groups of our readers would feel hurt or offended by the contents of your book,” replied the first editor to reject her manuscript for Lay Down Your Arms! and its bold calls for disarmament. She wrote in her Memoirs: “So I tried with another editor: the same result. And the same with others—unanimous rejections. One of the editors responded: ‘Despite all of its merits, publishing this novel in a military country would be very much out of the question.’”

Suttner eventually found a willing though hesitant publisher in Edgar Pierson. “Pierson advised that I should give the manuscript to some experienced statesman to look over and strike out everything that might give offense,” she wrote. “I cried out in indignation at such a demand. … To revise it under the guidelines of that most contemptible of all arts—the art of suiting everybody! No. I’d rather burn it in the stove first!”

To both Suttner’s and Pierson’s surprise, the published novel attracted a large global readership. Some major American newspapers even serialized the book during the early days of World War I. Other newspapers responded to the book with belittling reviews and caricatures. Despite its popularity (and probably because of it), Suttner’s work was, in the end, banned and burned. Nazi censors and other fascists hurled her books onto bonfires and destroyed many of her personal effects. Their goal was to erase the influential pacifist from history. Given how few people today are aware of her achievements, they largely succeeded.

In addition to gun-control advocates, the modern American Republican party has also targeted the GLBTQ+ community for censorship, forbidding access to transgender health care and, like Russia, criminalizing material that might be construed as promoting non-traditional lifestyles. Suttner was no stranger to controversy on these fronts, either. Publishing under the pseudonym B. Oulot, she adopted the persona of a male narrator in her novella Es Löwos, an intimate portrayal of a gender-equitable relationship. The title itself resists any strict translation from the German and imagines a creature that is neither a male lion nor a lioness. At one point, Suttner even outlines a grammar for this namesake animal—well over a century ahead of those promoting non-binary pronouns and transgendered identities:

So I created a new pronoun. The necessary inflections fell into place:

Nominative: Es. (Contemporary American equivalent: They.)

Genitive: Ems. (Their.)

Dative: Em. (Them.)

Accusative: En. (Them.)

For example: Es is coming. I will comb Ems mane. That belongs to Em. I love En.

(From Es Löwos, working translation by Hugh Coyle and Liz Sheedy)

Then as now, many (mostly conservative male) readers were horrified by the suggestion of variable gender roles and pronouns. Likewise, Suttner’s proto-feminist attitude and her frank discussions of sexual intimacy shocked some critics. “One does not expose such privacies to the multitude!” one complained, to which Suttner responded, “As if one writes for the multitude!” Instead, she envisioned an audience of sympathetic readers, “those in whom a string tuned to the same note is vibrating.”

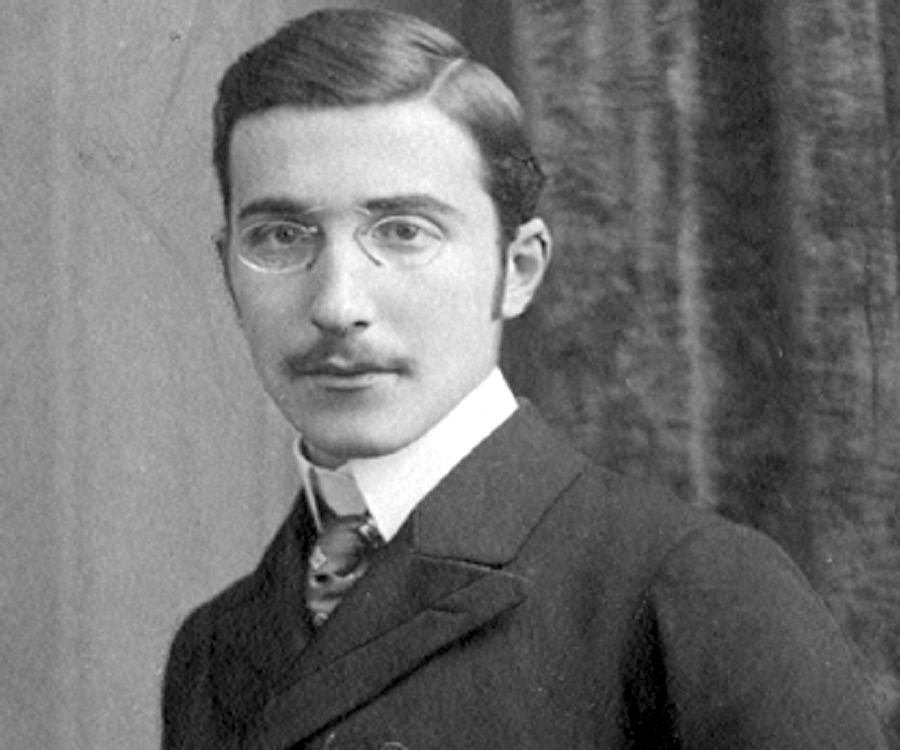

Suttner’s long-term friendship with Nobel suggests that he, too, felt similar vibrations upon reading her work. An intensely private lifelong bachelor, his love life remains a shrouded mystery. Historians have proposed numerous theories to explain Nobel’s enigmatic relationships with women (Suttner included), from an early case of syphilis and the side effects of its treatment to latent homosexual tendencies. A museum curator shared an anecdote with me of a scholar who was told outright that she could not make any reference, pro or con, to Nobel’s sexual preference at a Russian historian’s conference. (NB: The Nobel family has deep ties in Russia, and Alfred spent part of his youth in St. Petersburg.)

Radical right-wing school boards in various U.S. states have already banned books for merely acknowledging homosexuality. Fearing the right-wing censorship panels now spreading like a plague across the United States, some publishers have enacted preemptive strategies and asked authors to “clean up” manuscripts, removing any material that might provoke controversy. Classics, too, have fallen prey to the revisionists’ red pens. In crafting a fictional narrative based on well-documented research, I feel I can neither dismiss nor overlook the possibility that Alfred Nobel was gay. The complexity of his character will remain intact despite the complaints of some prudish overseers.

From its strong central message of disarmament to its depictions of non-normative sexualities, Peace at Last seems destined to follow in the footsteps of Suttner’s work and rankle its own crowd of authoritarian detractors. Though I had originally envisioned a novel that might pull together opposing political parties, the rising levels of polarity dividing the world today present an ever more daunting challenge.

“Persist, persist, and continue to persist,” Suttner once wrote in response to the many threats endangering the pacifist movement of the 19th century. Her stubborn defiance still shines brightly and provides a beacon of light and hope for those of us working to preserve and promote her peace-seeking legacy.